Stories

Martin Sharp AM (OC 1959), "Australia's Andy Warhol"

This article was written by Lyndon Goddard (OC 2007) for the Old Cranbrookians' Association and first appeared in the OCA Newsletter, December 2013.

On December 1, Cranbrook lost one of its most distinguished alumni and Australia lost one of its most celebrated artists in Martin Sharp (OC 1959).

For this special article, the OCA has received contributions from Juno Gemes, mother of Orlando Gemes (OC 1992) – Martin's godson – and a close friend of Martin’s for 50 years. Juno, an artist and photographer, has provided reflections on Martin’s life (incorporated below) as well as rare photographs from her personal collection. She has also allowed to be published for the first time a reflection on Martin’s famous 1975 ‘Portrait of Tiny Tim’. It can be found on our website here.

Recently described as ‘Australia’s Andy Warhol’, Martin Ritchie Sharp occupied a rarefied position in the country’s (and the world’s) artistic landscape, even though he was slow to be accepted as a major artist by the Australian establishment. This, however, did not concern the famously anti-establishment Sharp.

Nevertheless, the influence of Martin Sharp can partly be appreciated by noticing the international reaction to the news of his death, which was reported as far afield as France, Greece, Hungary and the Netherlands. France’s Le Monde, for example, described Sharp as an artist who was ‘symbolic of psychedelic rock’ and whose posters and album covers of the 1960s had become ‘classics of musical iconography’. Indeed, Fairfax art critic John McDonald recently wrote that Sharp was ‘the one local artist who you could mention to somebody in London, New York or Paris, and get an instant response.’

In a 1979 interview with fellow Australian artist James Gleeson, Martin traced his attraction to the pop art movement to his early fascination with comic books, which – while learning to read – he preferred over ordinary books. Another formative influence was the art of Vincent van Gogh. Though Martin’s later work was complex and infused with surrealist overtones, it was the direct simplicity of Van Gogh’s work that the young Sharp found ‘accessible’.

This interest in Van Gogh was spurred on by his experience at Cranbrook. Although he was born in Bellevue Hill and lived next door to the school, he attended as a boarder from the age of 12. He was fortunate to come under the tutelage of art teacher Justin O’Brien, himself a respected artist (having recently won the inaugural Blake Prize for Religious Art) who also nurtured the talents of John Montefiore and Peter Kingston during their time at the school.

Even while at Cranbrook, Sharp seems to have been something of a rebel. Juno Gemes remembers: ‘I met Martin Sharp when we were spectators at a cricket game at Cranbrook. He was 17 years old and I was 15, home from SCEGGS Moss Vale where I was a boarder. Martin had the appearance of a French movie star even then: wry and witty, sophisticated, elegant, and with that wide knock-out smile! We soon discovered we had much in common as eastern suburbs rebels – members of a bohemian circle of artists, writers, cartoonists – all wanting to shake Australia awake during the dull and rigid boredom of the Menzies years.’

Sharp once described Justin O’Brien as his ‘art father’ who taught that the practice of art was the pathway to fulfillment. As an art prize during high school, Sharp was awarded a copy of Lust for Life, a biographical novel based on the life of Van Gogh. There began Sharp’s fascination with the post-Impressionist artist, who influenced Sharp's work for decades afterwards – Sharp would often rework Van Gogh’s images as the basis of his own art. In fact, Sharp was probably surrounded by Van Gogh even before he started at Cranbrook – the doctor’s surgery of his father (a dermatologist) featured a reproduction of Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait on the Road to Tarascon, a painting that was destroyed during WWII. Sharp reworked this image throughout his life.

From O’Brien, Martin also learned classical drawing technique, which assisted him in composing his first series of portraits, completed while he was still at school. As Juno Gemes says, ‘Martin often talked of his affection for Justin O’Brien as a great art teacher who had a profound effect on him. Martin’s early portraits even then reminded me of the early works of Vincent van Gogh: astute, witty and compassionate; yet critical social commentary is subtly apparent in the work.’

After leaving school, Sharp’s art quickly began to attract attention. He first studied at the National Art School and then briefly at the architecture department of Sydney University, and in 1962 he co-founded the underground magazine Oz with Richard Neville and Richard Walsh. With Sharp as the art director, and self-described as a ‘magazine of dissent’, the publication soon acquired a national following.

The magazine’s reputation as anti-establishment was perhaps solidified a couple of years later when Martin and the two Richards were twice charged for printing an obscene publication – first for Martin’s satirical poem ‘The World Flashed Around the Arms’ and then for a cover which showed Richard Neville and two friends pretending to urinate into the famous Tom Bass sculpture ‘P & O Wall Fountain’ in Sydney’s CBD. The three editors were eventually acquitted.

It was not long before Sharp – like many other Australian artists and writers of that era – took his work to London. Juno Gemes remembers: ‘We were both drawn to the cultural revolution taking place in London in the early 1960s. We heard the music and the call. We were both of the first post-war generation, worldwide, who envisioned the possibility of another world – devoid of racism, sexism; based on cooperation, not competition.’

'A world economy not based on the global arms industry. We imagined a world where war would be obscene and unnecessary. We needed to communicate shared ideals far and wide by every medium we could find, or invent with others who thought similarly. Through Oz and his paintings, Martin was recognized as a major talent immediately, and a highly critical one.’

‘In London, we were part of the same world, the same scene. Martin lived at the Pheasantry on The King’s Road with Philippe Mora and Eric Clapton and a changing cast of women. Bob Whitaker had his photographic studio around the corner in Jubilee Place. I lived down the road in Chelsea at the World’s End. Almost daily I would call in at the Pheasantry. We’d talk about what we were doing, what was happening — while a then unknown guitarist called Eric Clapton played away in a corner of the grand room. Georges Mora told Martin at a young age that the best subject for art was art itself. His beloved mother Joan had taught him collage at an early age. These were the methods he employed so inventively in his work.’

‘London recognized that it had a resident genius artist in its midst, among the many emerging artists at that time. Poster art and record covers were the media of the day. Martin’s posters and album covers inspired, along with work by UK artists Nigel Waymouth, Michael English and Michael McInnery, Peter Blake. Their works were the jewels of ‘Underground Art’ in the UK. Most of these works are now in the Tate Britain and in the collections of museums worldwide as masterpieces of that era.’

During little more than two years in London, Martin relaunched the Oz there with Richard Neville, co-wrote the lyrics to Cream’s ‘Tales of Brave Ulysses’ with Eric Clapton, designed covers for that band’s Disraeli Gears and Wheels of Fire albums (the latter of which won the New York Art Director’s Prize for Best Album Design in 1969), and discovered falsetto singing phenomenon Tiny Tim, who inspired much of his work thereafter.

By the time that Sharp returned to Sydney in 1970, the New York Times had already reported – as Philippe Mora recalled recently in his eulogy to him – that Sharp had ‘decisively changed rock imagery’. That trailblazing was to continue back in Australia: shortly after his return, he rented a Victorian building in Potts Point, which became known as the ‘Yellow House’. For over two years, it was open 24 hours a day and hosted artists, writers and other creative spirits.

Juno Gemes also experienced this artistic Mecca: ‘On our return from London, we continued doing here what we had done there. Martin invited me to stay and contribute to the Yellow House. It was here that I began to understand what a profound influence the life and work of Vincent van Gogh was on Martin – indeed, the example of Vincent’s work and life continued to have an ever deepening effect on him to the end of his life.’

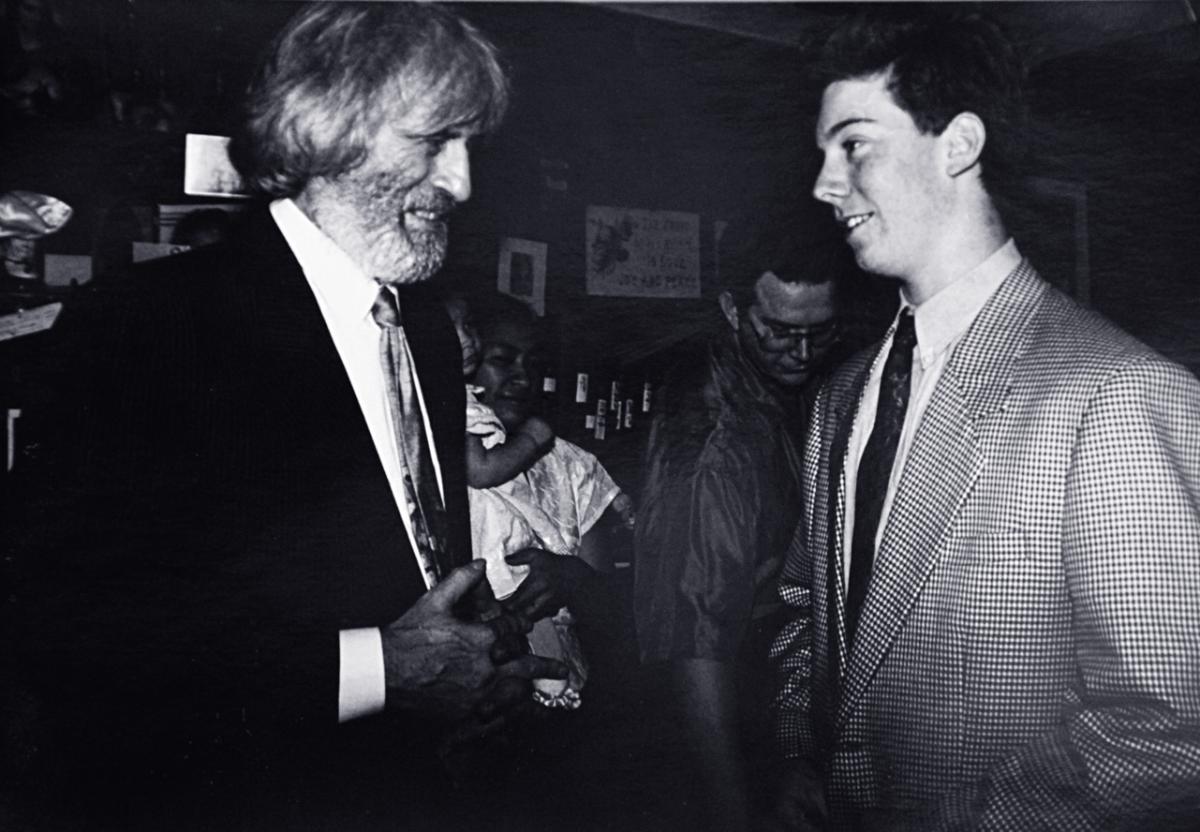

Juno’s son, and Martin’s godson, Orlando (OC 1992), was exposed to Cranbrook from an early age by Martin. ‘My son Orlando was born in London in 1975. Immediately, Martin showed a great affection and tenderness towards him. Orlando became one of Martin’s godchildren. When Orlando was 7 years old, it was clear to me he needed the stability of boarding school. We were recently back from London. I asked Martin, what should I do? We had often talked about how much the art classes at Cranbrook with Justin O’Brien had influenced him. Throughout his life, Martin’s interest and affection for Orlando continued as a sustaining influence. He took his role as godfather seriously, always inquiring about Orlando and his life.’

‘Martin suggested a tea party at Wirian. Martin and I made high tea for Mark Bishop, Joan Sharp [Martin's mother] and my mother Lucy Gemes. As we were having tea, Orlando sat on Mark Bishop’s lap and charmed him. Mark Bishop leaned forward and asked me, when would Orlando like to start at Cranbrook? Thus began Orlando’s life at the school. This story underscores Martin’s lifelong subtle kindness to his friends.’

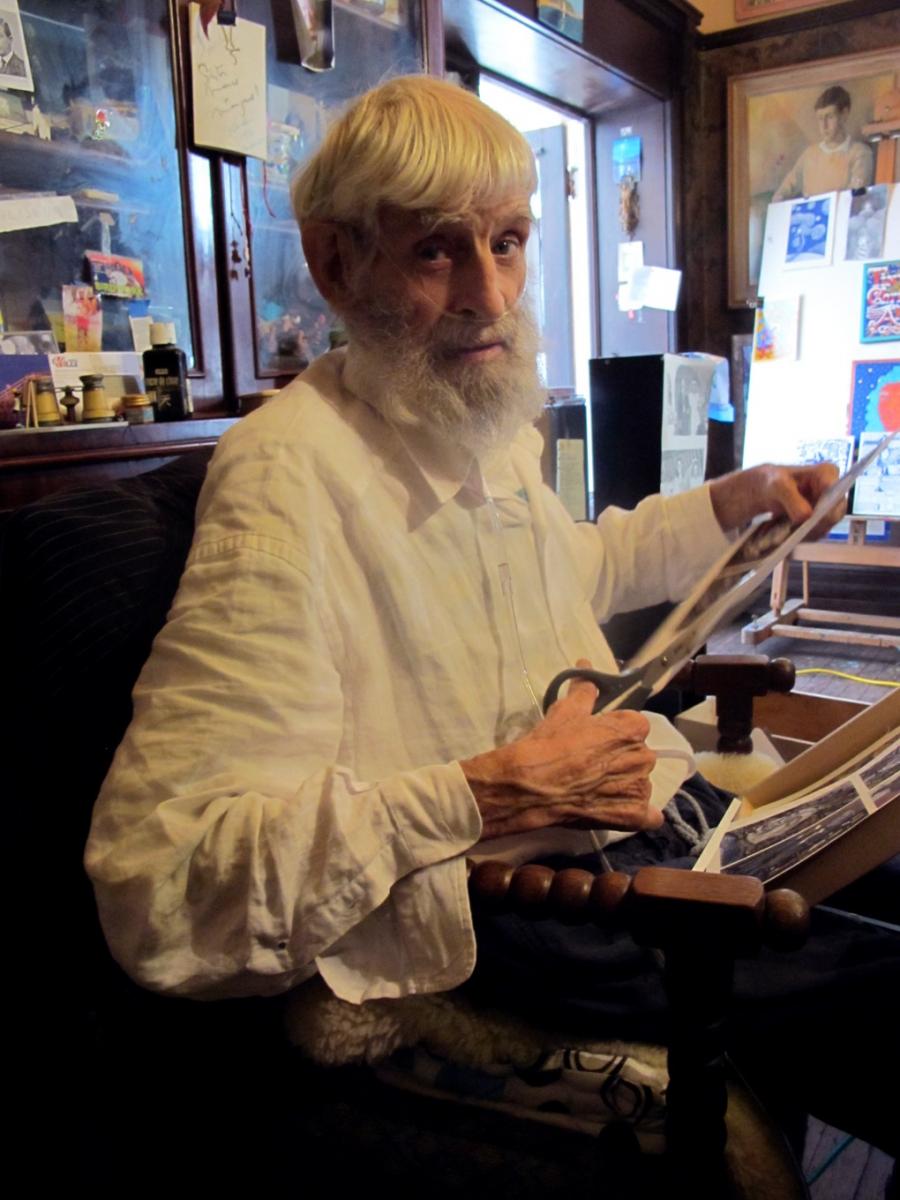

In his later years, Martin spent most of his time at Wirian, his inherited mansion next door to Cranbrook on Victoria Road. It became, in many ways, a larger version of the Yellow House before it, hosting innumerable visitors over the years while Martin continued to paint. Richard Neville described the dining table on which he primarily worked as ‘strewn with letters, postcards, drawings, cartoons, invitations and the previous night’s leftovers’ and the walls as ‘almost completely covered with paintings, scribbles, photographs’.

Martin Sharp leaves behind an impressive legacy indeed. The final words of reflection on Martin’s life are contributed by Juno Gemes:

‘Martin’s dedication to his art was the abiding dedication of his life. He told me so when we discussed the art/life axis. Because of his vast, varied and ingenious output and his reluctance to engage with the commercial art world, the art world found him hard to categorize and impossible to commodify.’

‘Unlike older cultures, Australia does not properly value its great artists as cultural wisdom holders and the inspiration they really are through their work – for everyone. Like Luna Park but not just for fun!’

‘I have a feeling that like one of his artist heroes, Vincent van Gogh, Martin’s star will shine in our eternity ever brighter as the years go on. Thanks Martin for all your great gifts to us, for your friendship and encouragement to a fellow artist, for your great contribution to Australian and world culture.’

Special thanks to:

- Juno Gemes, Artist / Photographer.

- Tom Kendall (OC 1992), for first mentioning the connection between Martin Sharp and Orlando & Juno Gemes.

![Martin Sharp in 1992 [photo credit: Juno Gemes].](https://cranbrookcentenary.com.au/sites/default/files/styles/story_picture/public/newsletter_martin_sharp_1992.jpg?itok=_86wNsu5)