Stories

Harry Nicolson, Teacher, 1946–1955 & 1966–1983

This extended article was written by Lyndon Goddard (OC 2007) for the Old Cranbrookians' Association and first appeared in the OC Magazine, March 2015.

One of only two people to have known every headmaster in Cranbrook’s history (the other being Frank Tebbutt), Harry Nicolson is a person for whom the phrase ‘part of the furniture’ is genuinely apt. He possesses an almost unparalleled longevity, an unstinting respect from his colleagues and students, and an intellectual rigour that is known as much for both its breadth as it is for its depth.

Although many people think of Harry’s time at Cranbrook as being virtually unbroken and never-ending, his career at the school was in fact divided into two stints. He began in 1946 (under Brian Hone), travelled to Europe on exchange in 1951-1952, and then left in 1955 to pursue a range of interests, including teaching at the Sydney Technical College. He came back to Cranbrook in 1966 (by which time Mark Bishop was headmaster) and retired in 1983, though he subsequently returned periodically to fill in for other teachers.

His connection to Cranbrook has not, however, dimmed in the intervening decades. He still attends Prizegiving every year, he is regularly invited to old boy reunions, and he continues to meet with each new headmaster – as he did recently with Nicholas Sampson.

Now in his tenth decade, Harry generously gave over two hours of his time to speak with the OCA about his career, his influences, and his thoughts on Cranbrook’s headmasters, its culture and the major changes that it has experienced over the past seventy years.

Much of the following article comprises paraphrased versions of Harry’s reminiscences, as supplemented by direct extracts from the interview transcript and from other sources.

Early life and commencement at Cranbrook

Educated at Sydney Boys High School, Harry Nicolson went on to study Arts (focusing on history and philosophy) at Sydney University and then went straight into teaching. When Harry was at school, he describes himself as having been “what they now call a nerd, I think”. He read a huge deal, and he was largely reliant on authors such as HG Wells for his background knowledge, such as from Wells’s book The Work, Wealth and Happiness of Mankind (1931). (Even today, Harry buys a new book about every second week.)

Before his career as a teacher, however, he had applied to be a parliamentary librarian:

But then I had to see the President of the Legislative Council, and he determined that only ex-servicemen could have the job. I’d previously applied for the air force and been rejected, so he couldn’t appoint me to the librarian job. So I was sitting for about two weeks wondering what to do. I used to work at Anthony Hordern’s in the layby department in the holidays, like most other students in the Arts faculty. I thought I’d have to apply for a Diploma of Education course. […] I was lucky that I’d known about Cranbrook because I did the university honours course in philosophy with Alan Stout [who had been on the Cranbrook Council].

When Harry started at Cranbrook in 1946, he took over from E J (Ted) Tapp, a New Zealander who had been teaching history and who had accepted a lectureship at the University of New England. Headmaster Brian Hone saw Harry on the Saturday before the first week of the school year and, having been asked by Hone, “What do you know about history?” (the reply was: “About as much as you”), Harry started work two days later. Some of the other teachers starting around that time, such as the Junior School’s Wal Potter, had only just arrived back home from war service.

Harry’s first four days on the job were spent sitting in with Ted Tapp in his classroom. Those four days constituting the entire extent of his teaching training, Harry then took over the class by himself, in Room 14 of the Perkins Building. Down the hall from him were A C Child and C A Bell (the former of whom later wrote Cranbrook: The First Fifty Years, published in 1968).

Harry soon found himself teaching a number of subjects: two honours classes in history; sixth form ancient history; upper fifth form modern history, ancient history and English; and remove in maths and history. In addition, he had library periods to run, in which he would introduce students to the Dewey system as well as teach general skills. In time, the library – to which Harry was an enthusiastic contributor – also produced its own magazine for senior and junior students, entitled Everyman. Later, he also became responsible for managing an array of extra-curricular activities for students, most notably his Greek Play Reading group and the Discussion Group. The latter was somewhat remarkable in that it was entirely student-run and met regularly to discuss all manner of topics – be they philosophy, history, or current affairs. The group was a popular one and, in Harry’s opinion, it played an influential role in the culture of discussion and debate at Cranbrook.

These commitments meant that Harry had very little time outside work. “I had an incredible load of marking when I started – some hundreds of essays to mark every week, and I tried to get some sort of written work from everyone, even the library classes. That really tied me down for the first couple of years, especially given that I also had to catalogue all the new books in the library.” The marking eventually also had an effect on his eyesight – but “when that marking burden was removed when I retired, my eyesight improved by three points within a couple of years!”

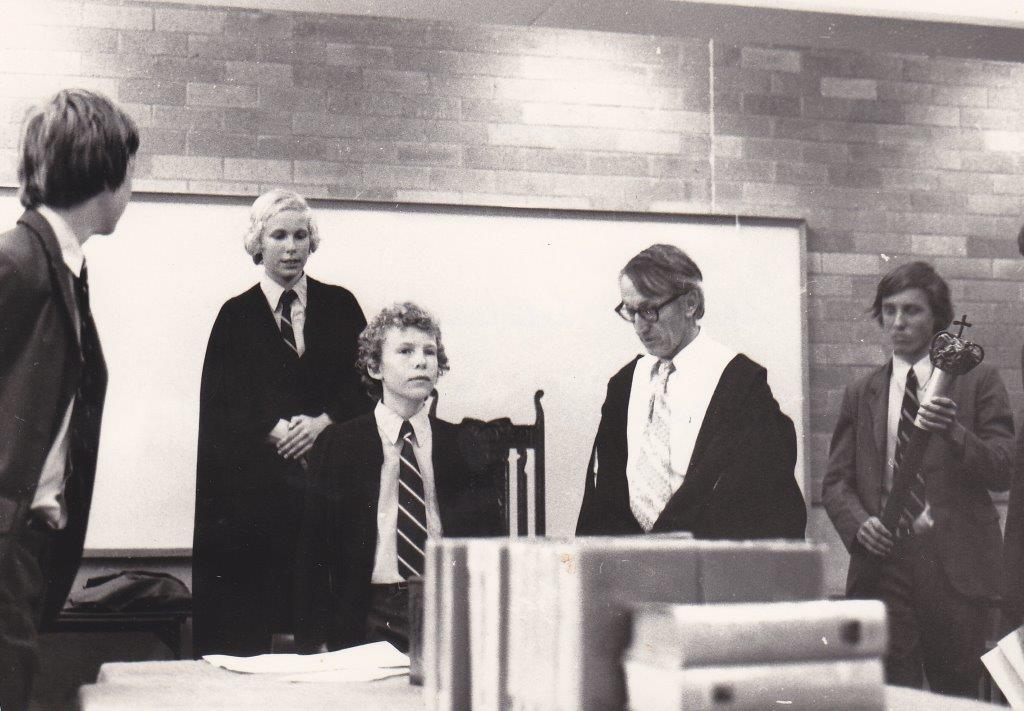

Harry Nicolson in 1981, organising a parliamentary debate with students.

Teaching style and the cane-eschewing disciplinarian

Part of Harry’s philosophy of teaching was to surround his students with visual material, so that, in his words, “they could swim in the pool of learning as much as possible”. His belief was that the students should be able to see everything that was taught in, say, ancient history. So he would build up picture sets from every magazine that he could beg, borrow or steal, and display them on the walls of his classroom. “It got to the point where I could illustrate every history lesson, so the class would always have some visual representation of what they were doing.”

Another facet of Harry’s teaching style, at least in the perception of his students, was that he was a disciplinarian. Harry explains: “I insisted that once you began the lesson, when the teacher talked, everyone else stopped. And if they started talking, I would stop talking. So if a student took up the class’s time by interrupting, I would take up his time by making him see me at break time or lunch.” As he would say to those who contravened that rule, “You’ve taken up our time; you pay up.”

However, he never once used the cane. That record is remarkable (and forward-thinking) when it is remembered that for at least the first half of Harry’s career, virtually every other teacher at Cranbrook used the cane, as it represented the accepted culture of discipline in both the school and in the educational community more generally. Indeed, when Harry arrived at Cranbrook, the teachers would have their cane suspended by two pegs in their classroom – no doubt to implicitly warn the students about the potential consequence of bad behaviour. Harry describes the system of discipline and his own practices in the following way:

The other teachers believed in [the cane], and they applied it fairly consistently, but about three years in, the rule became that boys had to be caned in the headmaster’s office, and it had to be entered in a book. But the prefects could still cane other boys, and that continued right up to Mark Bishop’s day. But I refused to cane from the beginning, and if a boy became really troublesome, I insisted that his parents be called in and we would have a discussion with the headmaster. I only had to do that on a handful of occasions.

It got about that I didn’t use the cane. I did yell at them now and again though, which I would never do now: I realize now that it’s a waste of time! So I was part of the revolution that eventually affected the whole community – and I was particularly strong on it because my two professors in philosophy were well known for their liberal opinions – especially John Anderson [Challis Professor of Philosophy at Sydney University]. He had a tremendous effect on me.

One memorable example of Harry’s discipline style was his management of the bus queues at the New South Head Road gates in the afternoon. From his reading of crowd behaviour, he had concluded that crowds (particularly of adolescent boys) got out of hand when they stood closely enough together to be able to touch each other. Hence, Harry would insist that the boys keep a space between themselves and the next member of the line, and that they not try to push through. And if any boy came out of the gate without his tie on, he would be sent back inside to get dressed properly. Common refrains included: “He who would be first will be last” and “Don’t touch the boy in front!”

Role in the Wyndham Scheme

Ever the academic, when he first started at Cranbrook, Harry used to take Friday afternoons off and read a piece of literature that was associated with the history syllabus. Interestingly, this practice eventually had an effect on not just his own students, but also on every student in NSW who studied ancient history. That is because Harry played an unusually influential role in the development of the new history syllabuses that were introduced in the 1960s as part of the ‘Wyndham Scheme’.

In 1953, Harold Wyndham, the Director-General of the NSW Education Department, was appointed to chair a committee to survey secondary education in NSW with the intention that the curriculum would be totally reorganized. For four years, the committee consulted widely, including with teachers’ groups such as the newly formed History Teachers’ Association of NSW (‘HTA’), of which Harry Nicolson was the deputy chairman in 1955. On 20 May 1955, Harry led a delegation of the HTA to a public hearing before the Wyndham Committee. He describes his subsequent work on the history syllabus thus:

The history syllabus was originally going to just be a rehash of the old syllabus, which had given a very big part to Australian history, one third of which was devoted to explorers, and there was a very poor course in the first year to introduce the students to ancient and medieval history. So I roughly explained to the Wyndham Committee the way that students should be introduced to world history. I knew Professor John Ward [professor of history at Sydney University and an influential figure in curriculum debates] pretty well, and he asked me to write a draft for the committee, and I did, and that essentially became the new syllabus. It made a complete break from the old syllabus and used an entirely new concept for the Australian history course and a new way of introducing world history to students.

The syllabuses in modern and ancient history that were established as part of the Wyndham Scheme are very similar to those that are studied today. The most important aspects of the Wyndham Scheme, as implemented, were that secondary schooling was extended from five to six years, a common core of subjects was introduced for the first year, elective subjects (at differing levels of difficulty) were provided for in the later years, and the structure and terminology of the School Certificate and the Higher School Certificate were introduced for the first time.

Harry Nicolson in 2014, attending the 1984 30-Year Reunion, along with other long-serving teachers David Thomas and Bill Roberts.

Teacher exchange to England: 1950-1951

During the 1950s in particular, under headmaster Brian Hone, Cranbrook’s teachers were regularly encouraged to participate in exchanges with schools in England. Harry describes Hone’s enthusiasm for this program as being because:

[he] believed in the exchange business. He himself had been a Rhodes Scholar – [and] he played cricket for South Australia – before he went to Marlborough College [to teach English for six years before coming to Cranbrook in 1940]. He saw the value of “acculturation”: just living with a school with a long tradition, and absorbing something of its vitality and bringing it back with you.

Far from there being a ‘cultural cringe’ element to this program, the rationale was that “if you just continued at one school all your life, you would miss out on a broadening of your outlook, obtained simply by living in another place”.

In December 1950, Harry was granted a leave of absence from Cranbrook for two years to study abroad, at London University and the British Museum. As The Cranbrookian recorded in 1956, “[b]oth there and in visits to the Continent, he was able further to enrich his store of knowledge of ancient history.” In 1983, The Cranbrookian described his time on exchange thus:

… he was not “on exchange”, trapped as some are in one school, but rather ranging widely through the ancient classical world or Rome and Greece, living freely in the Latin Quarter of Paris, working frantically in the British Museum and teaching for a time in Oundle and Repton Schools.

Time away from Cranbrook: 1955-1966

In 1955, Harry left Cranbrook to do things that he had not easily been able to do while working as a full-time teacher. He wrote three books with Professor A G L Shaw: An Introduction to Australian History, Growth and Development in Australia and Australia in the Twentieth Century. He taught in the Technical Education Department, and later became the Deputy Head of that Department’s School of External Studies following a spell as Head Teacher at St George Technical College. He was Chief Examiner and Assessor in Ancient History for the Leaving Certificate. He conducted refresher courses at Sydney Teachers’ College for six years. He lectured at the Philosophy Club. He lectured to tutorial groups at Sydney University on philosophy. He gave talks on the ABC. Finally, at East Sydney Technical College, he was invited to prepare and present lectures on the history of art.

By 1966, after some discussions, Harry agreed to return to Cranbrook. He became the Master in Charge of Library Activities, Master in Charge of Ancient History, Master in Charge of The Cranbrookian, Master in Charge of Tennis (for a short time), Chairman of the School Committee, and much more. There was a revival of the extra-curricular groups that Harry had managed – namely, the Greek Play Reading group, the Discussion Group, and History Society meetings and dinners – moreover, parliamentary debates were initiated and, of course, the New South Head Road bus queues became properly organized once more.

Experiences with Brian Hone

It is significant that someone with such a long history at Cranbrook as Harry Nicolson regards Brian Hone with great respect. When Harry first arrived at the school, however, he feared Hone as “a very authoritarian figure”. He says: “I was worried about the school’s general hierarchy – [an example of this being that] all the classrooms had platforms so that the master stood up above, and Hone would additionally have preferred all the teachers to wear gowns.”

Soon, Harry came to admire Hone’s unstinting energy that was poured into the school and his effectiveness in getting through to the students. (And later, when Mark Bishop was overseeing the construction of the new Senior School Building, Harry was able to influence him to build all the floors of the classrooms flat, so that the teacher was on an equal level to the students.) He explains that his view of Hone as an authoritarian figure has to be qualified by Hone’s ideal for the students: “While he quite rightly believed in the duty and responsibility involved in being the headmaster, and while he had a pretty heavy hand with the cane (from where he gained his nickname ‘The Blitz’), there was in fact much intermingling between him and the students.”

Some of that ‘intermingling’ with the students came not only from Hone’s meeting and talking with them in person, but also from his nightly practice of sitting in his study and reviewing their progress, such that, each week, he had reviewed every boy in the school. His goal was to discover each boy’s strengths and weaknesses, so that they could be individually managed. He also insisted that every teacher consult with every other teacher about every boy in the school, every term. Moreover, each term, he would attend the exam meeting for every subject to discuss the content and difficulty of the proposed exam. Hone also ensured that there was rigour and regularity in the provision of feedback on the students’ progress: for example, he introduced the report books, which provided information in the form of fortnightly ‘standards’, as well as a mark and a ‘standard’ each month.

While this extraordinary devotion of time may today seem practically impossible, it must be remembered that when Hone arrived at Cranbrook, the entire school comprised only around 270 boys, rising to about 350 by the time he left. Unsurprisingly, then, that was a method that could never be repeated today without a separate team of administrators dedicated solely to the task.

Hone’s high expectations for his students partly led to an amusing run-in with Harry in his fourth year as a teacher. Harry explains:

Hone introduced the idea that we should take off one mark in exams for every spelling mistake that a boy made. He came in to the common room and he mentioned it but didn’t give time to discuss it. And of course the idea was preposterous because we had a few boys with dyslexia (though that term itself wasn’t much talked about in those days), and boys like that would have ended up with no marks whatsoever had the new system been introduced. But at any rate, the system was brought in, and then Hone went around the common room and asked the teachers about how it had been received.

Everyone, including the senior master, told him that it hadn’t made much difference – but in fact they hadn’t actually applied the new system at all. I told him that I couldn’t apply it, and I gave him the names of the boys to whom it couldn’t apply, and he went red in the face and sat down. I continued, saying that the common room couldn’t be ruled in this way: we are in charge of each subject and we have to be able to make these sorts of decisions. And then he said, “This is rebellion!” and stormed out. I was able to avoid him for about four weeks after that!

The significance of that outcome was that it demonstrated a change in Cranbrook’s culture from that of an old English boarding school (in which the headmaster is utterly pre-eminent) to a more modern culture in which some authority was allowed to the teachers. Such was the reaction to Hone’s proposal that he never raised it again. (He did, however, discreetly ask C A Bell to raise it on his behalf among the teachers in the English Department.)

All of these practices are demonstrative of Hone’s deep interest in the development of his students. That interest manifested not just in his individual review of the boys, but also in his one-on-one interactions with them. The ease with which Hone was able to speak to students and get through to them was, according to Harry, one of his best traits as an educator. As Harry explains:

Hone had a way of coming down to the parapet in front of the room beside the Chapel. He used to stand there and gather the students around and talk about things [such as how to behave properly on a sporting field], so that the students came to understand how to be a gentleman and how to act towards his opponents.

Tellingly, in 1951, when the students heard that Hone was to move to Melbourne Grammar School to become headmaster there, a few boys went into his study and said, “Sir, we would like to come down with you so that we can deal with anyone who gives you trouble.”

Experiences with Mark Bishop

In addition to Brian Hone, Mark Bishop was the other headmaster who served for the most significant length of time during which Harry taught at Cranbrook.

Mark Bishop came to Cranbrook steeped in chemistry. His father had been the chief chemist at Arnott’s Biscuits, and was responsible for inventing the Arrowroot biscuit (as well as a few others). His method of teaching chemistry was to begin by having the students learn about things around them. He might start, for example, with experiments on orange and lemon juice, from which he would build up the boys’ knowledge to understand the difference between acids and alkalis, and between solids and liquids.

During the first Christmas holidays that Mark Bishop was headmaster, he had laboratories built in the old Stables (now the Foundation office) in which every boy had his own section. During the latter part of the 1960s, when the atmosphere was heady with the ‘space race’ between the United States and Russia, large sums of money became available to schools to promote science in the classrooms (with the goal of producing the country’s next generation of researchers). Mark Bishop got in first and used the funds that he obtained to build the new science block – appropriately since named the Bishop Building.

Mark Bishop’s approach as headmaster mirrored that of Brian Hone (whom Bishop regarded as something of a mentor), in that he took on an enormous workload in order to devote as much individual attention to his students as possible. One of the best examples of this was his decision to take over the entire enrolment process himself – which, in Harry’s view, was far too much work for a headmaster. Bishop insisted that every new parent provide the school with their boy’s doctor’s birth statement, and what he discovered was that Cranbrook was (and had been) taking a significant number of boys who suffered from various physical conditions.

Moreover, he was among the first to take autistic boys (and to use the term ‘autistic’), and he consciously took boys who would today be described as dyslexic. He had a Welsh counsellor who would meet every boy and conduct an intelligence test in two parts: one that evaluated written IQ and one that evaluated non-written IQ. The ultimate outcome of this testing was that Bishop employed around fifteen part-time teachers specifically to assist boys with learning difficulties. Whereas Brian Hone before him would try to move such boys away from areas in which they struggled, Bishop consciously set out to provide assistance to them in a systematic way.

The culture of Cranbrook and the biggest changes over the past 70 years

Asked about the ethos of Cranbrook, and about who was most responsible for developing it, Harry’s answer is Brian Hone. Hone’s close observation of every boy in the school and his insistence on having every teacher join in on the discussion – while such practices cannot be literally replicated today having regard to the school’s size – arguably constituted a critical stage in the development of Cranbrook’s culture to ‘nurture the individual’.

Harry points to a few of the biggest changes at Cranbrook that have taken place in the past 70 years. One is the structure and appearance of the teaching spaces. In contrast to when Harry first started, today all the school’s classrooms have proper teaching equipment that is flexible and able to be used in both lecture-style and discussion settings. Whereas there was previously only one big common room for all the teachers, there are now (from Brian Hone’s introduction) many of them throughout the campus – one for each subject area.

Another big change was Hone’s introduction of a sixth form and ‘repeat’ year. (Before the Wyndham Scheme, there were five years of high school: remove, third, fourth, fifth, sixth and then repeat sixth form. Today, of course, all the years are labelled sequentially.) The biggest change of all, according to Harry, has been something that he had nothing to do with – the use of computers and technology generally in the classroom.

Harry believes that the culture of the school is very different now to what it was when he first started his career. Every year group, he says, somehow has a distinct flavour to it, which he picks up on from his attendance at each year’s Prizegiving. Notwithstanding that, he thinks that much of the same spirit of Cranbrook remains as it was in Brian Hone’s time. He describes that spirit as the school’s “attempt to find a modus vivendi for every kind of boy. I’ve known very few boys who haven’t settled in.” Indeed, he offers the example of Martin Sharp (OC 1959; see a profile here) as being someone who was able to succeed at Cranbrook despite, at first glance, being someone who might not have fitted in.

Conclusion

Such is Harry Nicolson’s sheer longevity and breadth of experience that any attempt to summarize his career in a few words is fraught with danger. Instead, the final words are left to two publications whose authors had the benefit of sustained first-hand experience with him.

In A C Child’s 1968 book Cranbrook: The First Fifty Years, Harry Nicolson is described thus:

He came, as a young man during Hone’s headmastership – a protégé of BWH [Brian Hone], and certainly an intelligent and interesting one. He had a particularly lively mind and during his years at Cranbrook, he made a valuable to contribution to the teaching of both history and English. He also acted as librarian and did much to reorganise the Library. In himself he is a most likeable person, friendly, and sincere. Possessing a highly critical mind, he has definite opinions on most things and they are always worthwhile.

When Harry Nicolson retired in 1983, The Cranbrookian of that year said the following:

Nicolson’s quizzical, sceptical, Socratic habits and methods never degenerated into the cynical. They challenged his pupils and his colleagues, enlightening both, if they were attending, even though it was late at night in Common Room or in his resident tutor’s study. His interests and knowledge inside the classroom were those of the scholar even as a beginning teacher. Outside the classroom on the stone verandah playing chess – and in meetings of the numerous clubs and societies which sprang up around him – his tastes were catholic, civilized and informed […] from Jazz Group to Discussion Group, to Greek Play Reading to leather work, to Everyman, to Library use and management, to playing tennis and ‘talking late’.

[…] For over 30 years, HDN has challenged the intellectual integrity of his pupils and his colleagues. He has and still does rebut all that is shallow or false, or unworthy in our attitudes and thinking to the greatest of all professions – school mastering.