Stories

The War Comes to Cranbrook

The Japs shelled Sydney on Sunday night,

Hoping to give us all a great fright,

But I’m sure they didn’t succeed.

They fired their shells, from a six-inch gun,

And for myself at least, it was all great fun,

As the shells screamed overhead.

Most of the shells they fired were duds,

Though I did hear one or two thuds

Caused by a couple of live ones.

A shell landed in the street behind us,

But nobody, nobody, made any fuss,

Because of the loud explosion.

This shell wrecked a couple of places,

But you could tell by the smiling faces,

That nobody worried at all.

The Japs very soon left us alone,

And immediately I was heard to moan,

Because the shelling was over.

The Shelling of Sydney, R. P. Silverton (Remove A)1

On a bitterly cold night on 31 May 1942, three Ko-hyoteki class midget submarines crept past an incomplete anti-submarine boom net and into Sydney Harbour.2 While the first two were detected and destroyed, the third sank the converted naval barracks ferry HMAS Kuttabul, leaving twenty-one sailors dead.3

One former boarder recalled hearing the “ear shattering explosion” rattle the school’s windows as he walked back to Harvey House after a day with his mother.4 A week later, Frank Tebbutt witnessed “quite a lot of fireworks” from the Rawson House verandah as two submarines bombarded Sydney and Newcastle.5 The shells failed to cause significant damage, but, despite the optimism of R. P. Silverton’s poem, the attacks left everyone shaken, certain that a Japanese invasion was just around the corner.

The outbreak of WWII on 1 September 1939 affected our students' schooling, as the school attempted to contribute to the war effort and prepare for invasion. Throughout the 1940s, Cranbrook suffered from a shortage of staff.6 The shortage of domestic workers was most pronounced after 1943, when all Australian citizens over the age of sixteen were required to register for national service.7 According to Hamilton Harvey Sutton, this was not necessarily an unfortunate consequence of the war, as it made him and his classmates “realise that we were part of the school, and we had to do everything we could to help it, which we did”.8 This included raking the driveway, taking out the rubbish and weeding the ovals.9

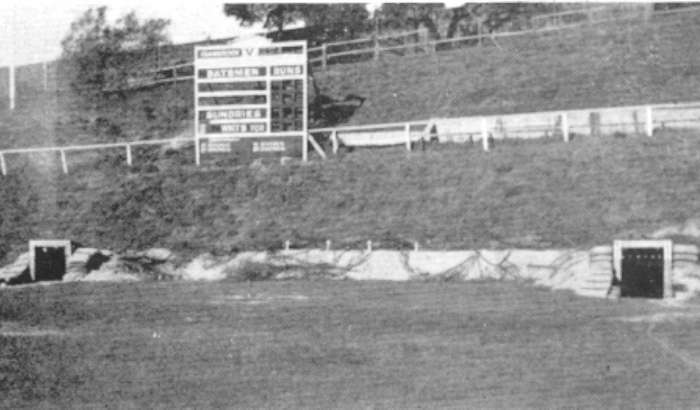

From 1943, the school's boys also helped to construct air raid shelters on the freshly weeded ovals and tennis courts.10 Contractors excavated the sand and built the shelters with “big wooden supports on the side”.11 The students then spent weeks piling the “huge heaps of excavated sand” on top of their galvanised iron roofs.12 Frank enjoyed this “reprieve from the classroom immensely”.13 The cellars under Rawson House were also fitted out and strengthened as a shelter for boarders and, after much practice, they became very efficient at evacuations – exiting the school and taking cover in just under five minutes.14

Despite such light-hearted recollections, it is clear that WWII demanded great personal sacrifice from Cranbrook's students. Looking back, past student and army officer Tim Bruxner regretted that his final year at Cranbrook in 1939 “wasn’t a good one” due to “the continual news coming from overseas”, and the despair of the parents, who “all had been involved in the first war”.15 He was disappointed to miss the opportunity to perform in the school play, due to the “more serious” cadet training required under the “certain knowledge that we were all inevitably going to be in the service ourselves”.16

Our school greatly admires the sacrifices that students like Tim made for our country, and the school spirit that students like Frank demonstrated. While the school magazine of 1939 despaired at the “narrowing of prejudices and jealousies” that had caused another global conflict, these Cranbrookians combatted war with the school values of service to others and action and team work.

- 1. R. P. Silverton, "The Shelling of Sydney," The Cranbrookian 23 (1942).

- 2. See Steven L. Carruthers, Japanese Submarine Raiders, 1942: A Maritime Mystery (Melbourne, Vic: Casper Publications, 2006); Peter Grose, A Very Rude Awakening: The Night the Japanese Midget Subs Came to Sydney Harbour (Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 2007); Bob Wurth, 1942: Australia's Greatest Peril (Sydney, NSW: Pan Macmillan, 2010); National Archives of Australia, "Japanese Midget Submarine Attacks on Sydney, 1942 – Fact Sheet 192", Australian Government, http://www.naa.gov.au/collection/fact-sheets/fs192.aspx.

- 3. "Australia under Attack", Australian War Memorial, https://www.awm.gov.au/visit/exhibitions/underattack/bombed/sydney.

- 4. Quoted in David Thomas and Mark McAndrew, Born in the Hour of Victory: Cranbrook School, 1918-1993 (Caringbah, NSW: Playright Publishing, 1998), 80.

- 5. Frank Tebbutt, "Memoir" (Cranbrook Archives, 2016).

- 6. Thomas and McAndrew, 74.

- 7. Ibid.

- 8. Hamilton Harvey Sutton, interview by Vicki Mesley, 1994.

- 9. Ibid.

- 10. "General Items", The Cranbrookian Vol. 22, No. 3 (1942): 3.

- 11. Harvey Sutton, op. cit.

- 12. Tebbutt, op. cit.

- 13. Ibid.

- 14. Thomas and McAndrew, 78.

- 15. Tim Bruxner, interview by Vicki Mesley, 13 January, 1994, interview S244/11.

- 16. Ibid.